04.06.2018

The works of art are attacked for various reasons – political, religious, or from anger and mental illness. But sometimes the destruction of another’s creation is seen as a way to create one’s own.

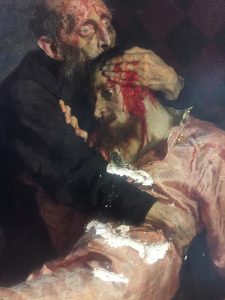

Painting by Ilya Repin “Ivan the Terrible and his son Ivan” after the visitor’s attack on May 25, 2018. The State Tretyakov Gallery.

Painting by Ilya Repin “Ivan the Terrible and his son Ivan” after the visitor’s attack on May 25, 2018. The State Tretyakov Gallery.

The most common reason for attacks on works of art is the expression of political protest. At least, the criminals themselves say that. On May 25 Igor Podporin hit the picture of Ilia Repin three times “Ivan the Terrible and his son Ivan” with a solid fencing, having disagreed with the content of the canvas exhibited in the Tretyakov Gallery, which represents the Russian king as a crazy tyrant. Mary Richardson, in 1914, cut the entire “Venus with a Mirror” back to Velazquez in the London National Gallery to draw attention to the rights of women. In 1985, Bronius Meigis poured acid into Rembrandt’s “Danube” in the Hermitage and declared himself a Lithuanian nationalist. In 2009, a Russian woman dropped a souvenir mug at the “Gioconda” in the Louvre – the mug collapsed on the protective glass; according to one version, the reason was the refusal to obtain French citizenship.

In the second place in the vandals, raped religious and ethical feelings. One hundred years ago, apparently, they forced Abram Balashov to shout: “Pretty blood!” – Landing with the knife of the same “Ivan the Terrible and his son Ivan”. The spectacle of Pieto Michelangelo in St. Peter’s Cathedral in Rome in 1972 caused the mentally unstable geologist to begin to crush the sculpture with a hammer, shouting: “I am Jesus Christ!” In 2016, Jock Storges’ work was poured into urine at the Lumiere Brothers Center in Moscow, suspecting the author of pedophilia .

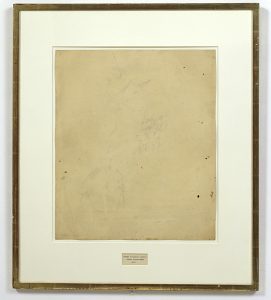

Robert Rauschenberg “Erased de Kooning Drawing”. 1953

Robert Rauschenberg “Erased de Kooning Drawing”. 1953

There are many such cases. However, there are examples of destruction of paintings or damage to them in order to create a new artistic work. So to speak, vandalism is an artistic way.

The most brilliant example is the famous “Erased de Kooning Drawing” by Robert Rauschenberg. In 1953, Rauschenberg, one of the founders of pop art, showed at the exhibition work titled “The Stripped Figure de Kuninga”. Indeed, it was a piece of paper with Willem de Kooning’s pencil sketch (his Rauschenberg received as a gift from the author). The meaning and value of this experiment have long been refuted: it is an attempt to cast doubt on the idea of traditional art. And can an independent work destroy the work of another artist?

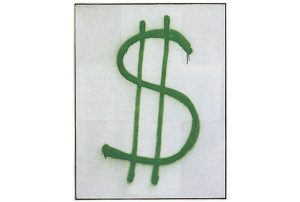

“Suprematist” (“White Cross”) (1920-1927) Kazimir Malevich after “dialogue” with Alexander Brener.

“Suprematist” (“White Cross”) (1920-1927) Kazimir Malevich after “dialogue” with Alexander Brener.

The Russian artist, Alexander Brener, allowed himself a much more radical gesture: in 1997, he painted a dollar sign on the green paint from the cannon on the suprematist “White Cross” by Kazimir Malevich. Since the case was in the Amsterdam Stedelayk Museum, while Malevich was worth several million, the art community was inclined to condemn this action and refused to accept the new work with dual authorship Malevich-Brener. The paint washed away, Brener sat. However, the idea turned out to be viable: a few years ago, a certain Vladimir Umants signed with his name the canvas of Mark Rothko to Tate Modern. Ai Weiwei beat the ancient Chinese vase; then another artist at the exhibition broke the vazai Ai Weiwei. In 1986, a certain artist cut into pieces the abstract canvas of Barnett Newman “Who is afraid of red, yellow and blue III” (also in the Stedelayk Museum). He was caught, he sat and returned nine years later to the museum to cut another picture.

“Improved” Jake and Dinos Chapmany portrait of an unknown artist of the 18th-19th centuries.

“Improved” Jake and Dinos Chapmany portrait of an unknown artist of the 18th-19th centuries.

Modern British artists, the brothers Chapman, made a loud project with “improved” portraits of unknown (and insignificant) artists of the 18th-19th centuries from their own collection – they depicted characters on them, they painted strange nose and ears, raising their value tenfold.

The case with “fluffy Jesus” turned out to be quite anecdotal – in the Spanish province, an elderly parishioner has so updated the head of Christ in the temple (in the composition “The man’s man” by artist Elias Garcia Martinez) that he became like a monkey shaggy. The image has become popular (they say, they even print on souvenir shirts) – while Martinez, who worked at the turn of the XIX-XX century, no one remembered.

Works of art are defenseless in front of the vandals, no matter what purpose they set before themselves, and no matter how glory they eventually reached. Even an act of sincere love can be detrimental – the traces of lipstick of the creator of expressionist Sai Twumbly could not be removed from the canvas exhibited at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Avignon.