02.08.2018

For an untrained eye, it looked like a piece of sticky tape. But for Jeannette Redensec, a scientist who examined hundreds of paintings in preparation for the exhibition of the German-American modernist Joseph Albers, a yellowed strip of glue, stuck on the back of one of the works, became a revelation. A modest scrap of tape gave the last clue that told the whole story of the picture. So, according to the inscriptions on a piece of paper, the owner of the canvas was a collector from Cleveland. Jeannette Redensec belongs to a separate subculture of world art, consisting of curators, conservatives, researchers and other market professionals who like to recognize the “reverse side of works of art.”

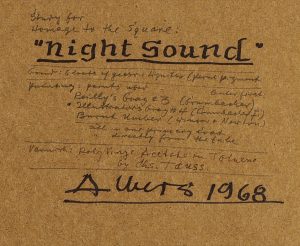

“On the reverse side of the picture can be stored almost as much information as on the front,” – said Cathy Rogers, president of the Association of Researchers Raisonné Scholars Association. The face of the picture conveys its art historical context, but its reverse often carries the history of the work itself. On the backs of canvases, stretchers and the lower side of the frame, attentive experts can often find inscriptions left by the artists. Very often such inscriptions are made by dealers, collectors and museums with designations, from greased pencil notes to wax seals, exhibition labels and inventory numbers. All these markings can be considered a passport of the picture, because they represent the personality of the work, its travels and even the change of address.

The artist’s notes usually serve as a means of ensuring that important information about the work, such as its title, date and authorship, is preserved as it is transmitted. But the practice is individual; some artists share more curious details or use both sides of the canvas. Artists, constantly altering canvases, can delete previously written on stretchers the old names, leaving hints on images disguised as layers of superimposed smears. “On the” Portrait of Saint Philip Neri “from the Metropolitan Museum Carlo Dolci left a few notes in which he says, when he began work on the piece, how long it took, and the fact that he started writing it on his birthday,” recalls Keith Christiansen, chairman of the department of European paintings in the Metropolitan Museum. Verso by Robert Motherwell. The French line of 1960. Provided by the Dedalus Foundation. For artists of the twentieth century, experimenting with abstraction, the backs of paintings were a convenient place to leave explanatory notes. For example, abstract artist-expressionist Motherwell sometimes left keys for decoding several layers of meaning in the title of the works.

On the reverse side of the collage called “The French Line” (1960), the artist detailed all possible interpretations of the picture: “1. Painting (French) / 2. Diets (amis fidèles de votre ligne) / 3. Boats (transatlantic) / 4. Cote d’Azur (shoreline). ” Restorers paid attention to the reverse side of works of art, at least from the end of the XVIII century, if not earlier. Aristocratic European collectors once minted their paintings with wax seals bearing the family coat of arms, canvas producers stamped their signs on raw materials, and auction houses branded their lots with peculiar alphanumeric configurations. For example, the French art dealer of the early twentieth century Ambroise Vollar, as a rule, recorded his inventory in blue pencil. Art, looted by the Nazis during World War II, also has such marks. Most often they depict a symbol similar to a two-headed eagle. Understanding these markings is important to confirm the authenticity of the picture or to increase its market value.

Source: http://art-news.com.ua/sekrety-skrytye-na-oborotakh-yzvestnykh-proyzvedenyi-19632.html

© Art News Ukraine. Under the guidance of Sotheby’s.